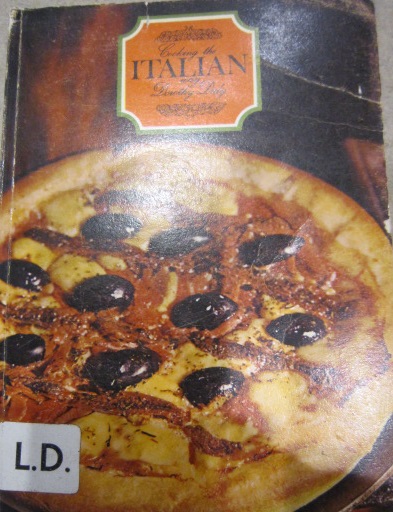

Dorothy Daly’s Italian Cooking has been cited as one of the first Italian cookbooks written in English. It doesn’t have a date of publication on it, but no less than the Boston Public Library (BPL) has declared it was published in 1900, at least according to the Open Library and Internet Archive, which would mean, like Janet Ross’ Leaves from our Tuscan Kitchen, it was indeed one of the first:

Except it wasn’t published in 1900. It couldn’t have been. It’s wrong and it’s making me crazy. So, how do I, a lowly PhD student, dare to doubt establishments such as the BPL? Well, here’s some proof:

Except it wasn’t published in 1900. It couldn’t have been. It’s wrong and it’s making me crazy. So, how do I, a lowly PhD student, dare to doubt establishments such as the BPL? Well, here’s some proof:

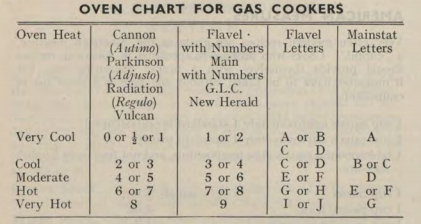

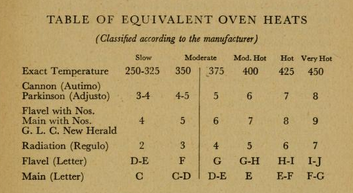

- The book includes a “Table of Equivalent Oven Heats” which features heat settings for different manufacturers’ ovens. Not only does it seem like one oven, the Cannon with Autimo settings, didn’t exist until at least the late 40s, Daly’s chart also bears a striking resemblance to one published in the 1950s by British food writer Ambrose Heath in Kitchen Wisdom:

The oven temperature chart in Dorothy Daly’s Italian Cooking features some ovens that didn’t exist till after World War II…

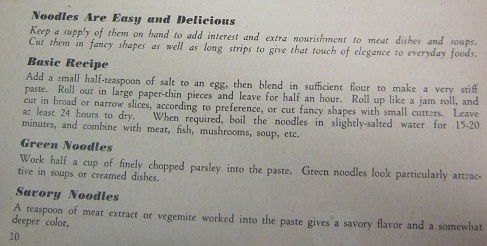

- It repeats as fact the myth that Marco Polo brought pasta to Italy from China, a myth which a number of scholars believe came from a 1920s item in the Macaroni Journal, a trade publication for pasta makers in the US.

- Daly uses the term “pasta” throughout the book, but this word was not in common use in English-language cookbooks until at least the 1950s, with “macaroni” the preferred umbrella term for different pasta shapes up until then.

- Sun Books published an Australian edition in 1969 under the title Cooking the Italian Way. Except for the title, and some minor editing, there isn’t much difference between this version and the so-called 1900 edition. It seems pretty unlikely that a book would require little editing when so much has changed in the kitchen from 1900 to the late 60s, unless it was marketed as some kind of nostalgia trip, which it wasn’t. Much more likely is that the book was first published in London in the late 1950s, which British historian Panikos Panayi notes in Spicing up Britain: The Multicultural History of British Food.

- The illusive Ms Daly also wrote a bunch of other books on Italy, all of which feature publication dates in the 1950s, 60s, 70s and even 80s. Some of these are reprints, but unless Daly was a prolific genius writing from the age of 2 until her old age, it’s difficult to account for the fact that the rest of the woman’s work was published 50 years after her first book. Incidentally, I have found very little biographical information about the mysterious Dot Daly, like when she was born and when she died, so if you know something, say something.

- Stylistically, typographically and linguistically Italian Cooking just doesn’t look or sound like a book written at the turn of the last century. Don’t believe me? Have a look yourself and you will no doubt find a hundred other reasons why this book couldn’t have been published in 1900.

So this wrong date is now all over the Internet, with some categorising it incorrectly, even Google, and others trying to make a quick buck. It makes me mad, not because people are potentially getting ripped off, although that’s never nice, but because a wrong date can lead a student of history to make incorrect assumptions about, well, everything. It also proves you can’t just accept what other people – even if those people are big, established, respected libraries – say. You have to question everything. Though, let’s be honest, we could’ve saved a hell of a lot of time if the publisher HAD JUST PUT THE DAMN DATE ON THE BOOK IN THE FIRST PLACE!

Sorry for yelling, but I was angry. I feel better now.